Volume Rendering

CS 481/681 2007 Lecture, Dr. Lawlor

So we've seen tons of rendering using Triangles. Last week we did

a lot of Point rendering. Today we do Volume rendering. You

need volume rendering to render objects without well-defined surfaces, like clouds, smoke, or fire. It's also useful for examining 3D datasets, like MRI or CAT scans.

The Right Way to do Volume Rendering

Walk down a light ray. At each point in 3D space, the light

interacts with the scattering medium. Depending on the

assumptions, you can usually write this as an integral as a function of

distance along the light ray. If the scattering medium is simple,

you can analytically solve this integral. For example, the

integrated amount of light accumulated along a path through uniform

glowing fog is proportional to the distance you've travelled through the fog. This is hence really easy to compute--find the distance from the camera to the object, multiply by a constant, and there's your fog.

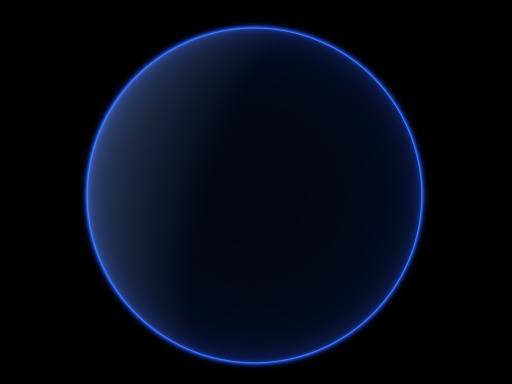

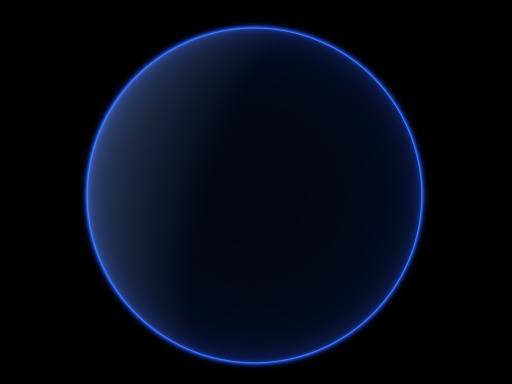

I was really happy to figure out that if the density of a planet's

atmosphere changes exponentially as a function of radius, then you can

actually approximate the atmosphere density along the ray with the

exponential of a quadratic polynomial of the ray parameter, which you

can then evaluate exactly using the "erf"

math library routine. This, combined with a simple

raytraced-spheres path calculator, lets you produce cool planets

without too much computing:

Unfortunately, for interesting distributions of light, it's often not

possible to analytically evaluate the volume rendering

integral. For example, in the image above, the atmosphere

is a uniform glowy color--accurate for a self-luminescent radium

planet, but wrong for a normal sunlit globe. In general, for any

distribution of light you can't analytically evaluate, you're stuck

with...

The Usual Way to do Volume Rendering

Walk down a light ray. Take discrete steps. At each point

you sample, let the light interact with the scattering medium.

See the difference? We've turned an infinite number of sample

points (a continuum problem) into a finite number of sample points (a

discrete problem). If we just wave our hands and say "as the

number of sample points along each ray goes to infinity, we eventually

approach the right answer" even though our framerate will drop to zero!

There are lots of ways to take discrete steps. You can literally

create rays and add in sample points--this is common in software

renderers. You can switch the order of rendering around and first

figure out what happens on the first step of all rays, then what

happens on the second step of all rays, and so on--this amounts to

drawing the volume as a series of alpha-blended texture-mapped planes,

and is a really common way to render stuff on the graphics hardware.

One problem with doing anything discrete in 3D is the data size--a 1024^3 volume is one billion

samples! Even a really coarse 128x128x128 volume is 2 million

samples. This makes it tricky to store or render high-resolution

volume datasets, although a low-res dataset does work OK.

Volume datasets usually compress pretty nicely as well--I usually stack

all the volume slices into a very tall skinny 2D jpeg, which seems to

work nicely.

How does Light interact with a Volume?

In principle, anything could happen to light while passing through a volume:

- The medium could emit light. This is easy--just add the emissive color to the old color.

- The medium could reflect light. This is really tricky in

general (volume global illumination), but you can do a reasonable job

for one-bounce effects from simple directional light sources by

approximating a normal (usually via the volume's density gradient) and

then shading each point in the volume the same way you shade a normal

2D surface. Diffuse reflections look fine, and even specular

reflections do OK at low specularity or high volume resolution.

- The light could be absorbed (beta, extinction). This can be

approximated fairly well by alpha-compositing the voxel color over the

old light color.

Source of Volume Datasets

I've got a bunch of datasets in "tall skinny JPEG of stacked slices" format

here.

Stefan Röttger at the University of Erlangen has a cool Volume Dataset Library. His volume-rendering software V^3 is pretty cool too, although the viewer only runs on nVidia boxes because he uses NV_register_combiners, the creaky grandpa of programmable shaders (ARB_fragment_program is the over-the-hill baby boomer; and GLSL is the flashy hip new kid).