Simple CPU Design

CS 441 Lecture, Dr. Lawlor

Silicon FET Transistors

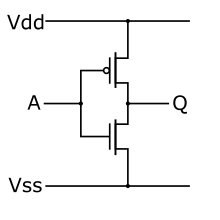

Modern transistors are FET transistors:

you charge up a small channel called the "gate", and it conducts

current between two terminals. In an "n-channel FET", the gate

already has plenty of electrons, so you need to discharge them with a

positive voltage to allow it to conduct. In a

"p-channel FET", you open the gate with a negative voltage. I

like Wikipedia's pictures for these: n-channel is a positive logic

input, and p-channel is an inverting input with an inverting circle.

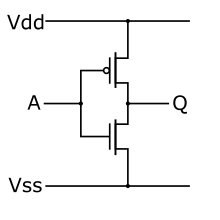

You can build logic gates from FET transistors quite easily in a "totem pole" configuration. Here's an inverter:

When A is positive, it turns off the high gate, disconnecting Q from

positive voltage (Vdd); and turns on the low gate, connecting Q to the

negative voltage (Vss): A positive makes Q negative. When A is

negative, it turns on the high gate and off the low gate, connecting Q

to positive voltage and disconnecting negative voltage; A negative

makes Q positive.

Here's an AND gate built from FET transistors, and the corresponding silicon implementation:

It's quite easy to build all the logic gates with FET transistors!

Circuit Simulation via TkGate

We're really not going to do spend much time designing actual digital

circuits (this isn't an EE course!), but it's important to understand

the general way digital logic circuits work.

The easiest way to do this is to just play around with circuits for a

few hours. I've prepared the examples below using TkGate, a UNIX-ey

open source digital logic designer and simulator.

- In Windows, TkGate is only available via the UNIX compatability layer Cygwin, but it is built in to Cygwin.

- In

Linux, TkGate is often available from your package manager (in Ubuntu,

"sudo apt-get install tkgate; sudo ln -s /usr/bin/

/usr/share/tkgate-1.8.7/libexec").

- In MacOS X, supposedly TkGate can be built from source, which you download here.

The TkGate Documentation is pretty good, and the program runs a simple tutorial when you start it.

Many other circuit simulators exist. In EE 341, I used "LogicWorks",

which is a fine commercial program for Windows and MacOS. Sadly, translating

circuits between two graphical simulator packages is only rarely possible!

Simple CPUs built from Digital Logic Circuits

Here are a few steps on the evolutionary path to a CPU:

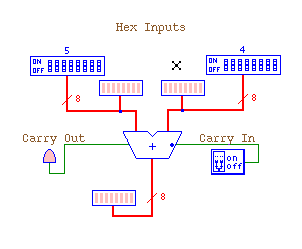

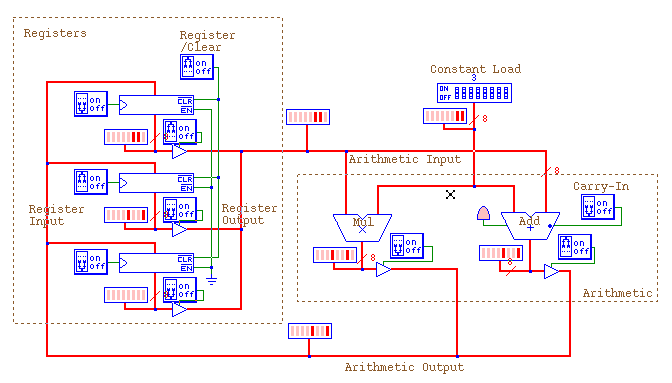

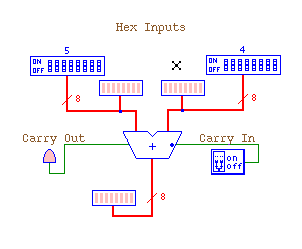

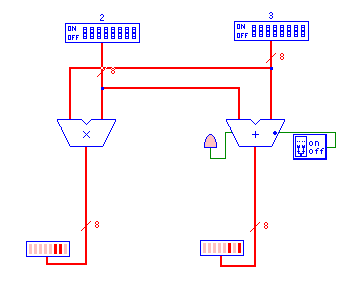

First, an add circuit. We've set up two 8-bit hex input devices

(DIP Switches) in TkGate, hooked them to a Make -> ALU -> Adder,

and displayed both input and output binary data in 8-LED arrays.

Click the above circuit to download the TkGate Verilog-style circuit

description.

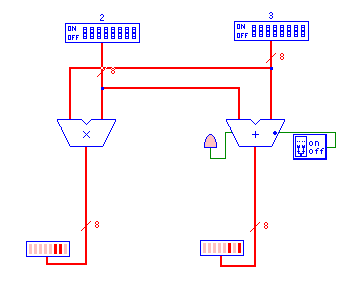

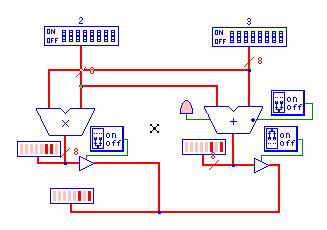

Here's almost the same circuit, except now we run the input values past a multiply circuit as well as the adder.

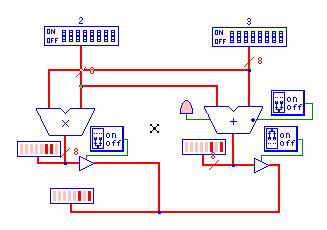

Now we've added a "bus". The little three-input triangles below each arithmetic unit are "tri-state buffer/drivers",

which enable us to turn the add and multiply outputs on and off, and so

combine the outputs of these two circuits. The idea is we turn on

the output we want, which at the moment we do manually, by flipping the

appropriate output switch. If you turn multiple outputs on at the

same time, or turn no outputs on, TkGate shows a yellow indeterminate

output state. In real circuits, driving a bus to several

different values causes the buffer drivers to heat up and possibly fry

themselves!

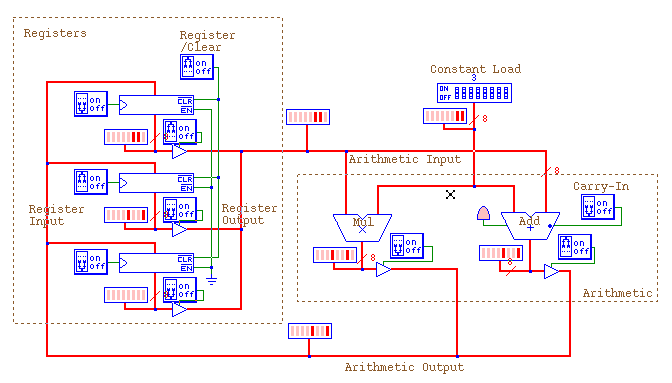

Now we add a set of "registers", which are just data storage

elements. We hook up the output of each register to a tri-state

driver, and use the drivers to select which register we want to read as

input. We hook up the data input to each register to the

arithmetic output bus. Finally, we can manually "clock in" the

arithmetic result into any register (via the triangle-shaped register

inputs).

Annoyingly, TkGate starts all the registers in indeterminate (yellow)

state, rather than zero, so we have to manually clear the registers at

simulated startup by flipping the register clear switch off and then on

again.

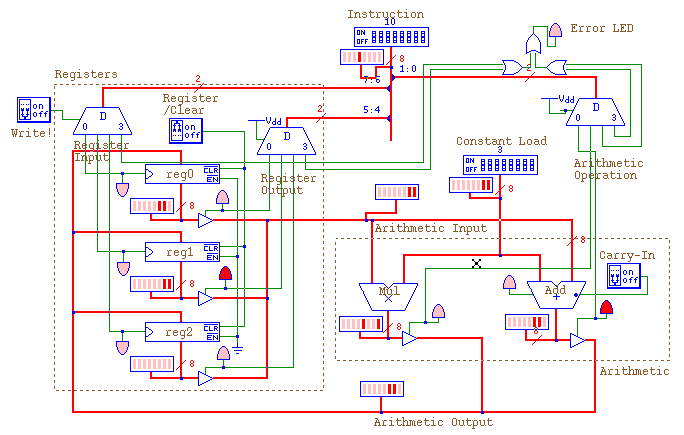

OK, now we're approaching a real CPU! The only thing we're

missing is a control unit that will flip all the switches appropriately

to execute some instructions!

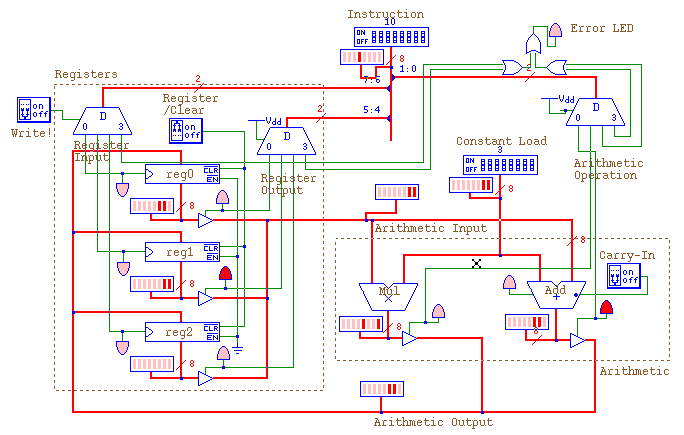

The big trapezoidal "0 D 3" modules are called decoders

(also known as demultiplexors or demuxes). They take a binary

input value (the red bus going in the top), and copy the left input to

one of the four outputs along the bottom. We've wired these mux

outputs to the input lines of our arithmetic bus, register output bus,

and register input bus. This means that rather than manually

flipping switches, we just need to load a binary number into the

"instruction" register!

In this case, we've connected bits 1:0 (the low two bits) of the

instruction to the arithmetic operation demux. So if the low bits

are 00, the add circuit turns on. If the low bits are 01, the

multiply circuit turns on. Bits 5:4 (the low two bits of the high

hex digit) connect to the register output. So 00 means output

register 0 to the arithmetic input bus, 01 means output register 1, 10

means output register 2, and 11 is an error. Finally, bits 7:6,

the high two bits of the instruction, connect to the register input

control lines. To write to register 0, the high bits should be

zero, and so on. You need to manually flip the "write" switch to

make the registers write (this avoids annoying circuit race conditions).

So overall, this CPU's instructions look like:

<destination register: 2 bits>

<source register: 2 bits> <unused: 2 bits>

<operation: 2 bits>

<constant: 8 bits>

For example, the instruction (hex) "40" (binary 0100 0000) writes to register 1, reads from register 0, and adds.