Vector Partial Differential Equations & Navier-Stokes

CS 493

Lecture, Dr. Lawlor

Vector Calculus: Div, Grad, Curl

For reference, you often see these vector calculus symbols in PDEs:

Symbol

|

Pronounced

|

Mathematical Definition

|

Input

Output

|

Meaning

|

∇A

|

"gradient A"

"grad A"

or "del A" |

vec3(∂A / ∂x,

∂A / ∂y,

∂A / ∂z) |

scalar

vector

|

The gradient

vector points in the direction of greatest change.

|

| ∇ . A |

"divergence A"

or "div A" |

∂A.x / ∂x +

∂A.y / ∂y +

∂A.z / ∂z |

vector

scalar

|

Positive divergence

indicates areas where a vector field is leaving.

Negative indicates convergence, where field is arriving.

|

| ∇ . ∇ A or ∇2A

or ∆A |

"laplace A"

or

"div grad A"

|

∂2A / ∂x2 +

∂2A / ∂y2 +

∂2A / ∂z2 |

scalar

scalar

|

The Laplace

operator shows up in diffusion,

and other energy minimization problems.

|

| ∇ x A |

"curl A"

"vorticity A"

or "rot A"

|

vec3(∂A.z / ∂y - ∂A.y / ∂z,

∂A.x / ∂z - ∂A.z

/ ∂x,

∂A.y / ∂x - ∂A.x

/ ∂y) |

vector

vector

|

The curl

operator measures local rotation.

The magnitude of the curl indicates rotational speed.

The direction of the curl indicates the rotational axis.

|

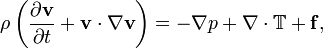

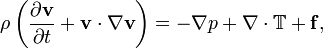

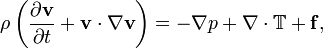

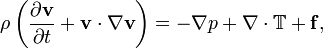

Navier-Stokes Fluid Dynamics

For example, Navier-Stokes

fluid dynamics is:

The variables here are easy enough:

- v is the fluid velocity. It's a vector, and hence

written in bold.

- ρ, the Greek letter rho, is the

fluid density: mass/volume. It's there because this

equation is

actually "m * A = F" (rearranged F=mA).

- p is the fluid pressure.

- T is a stress tensor, used for viscous fluids. If

viscosity is zero, you can ignore this term.

- f are any other forces acting on the fluid, like gravity or

wind. Calling these "body forces" makes them sound more

mysterious and intimidating.

As we saw above, "∇ p" means a gradient:

∇ p = del p = vec3(∂p / dx, ∂p

/ dy, ∂p / ∂z)

This converts a scalar pressure, into a

vector pointing in the direction of greatest change. The

magnitude of the vector corresponds to the pressure difference.

We've seen this "pressure derivatives affect velocity" business in

our

little wave simulation program, where we're updating the current

velocity:

vel.x+=dt*(L.z-R.z); /* height

difference -> velocity */

vel.y+=dt*(B.z-T.z);

Written more mathematically, we're really doing this computation.

dv / dt = vec2(L.b-R.b,B.b-T.b)

Recall that from the Taylor series, we can approximate the pressure

derivative with a centered

difference dp/dx = (R.b-L.b)/grid_size. Say both the

grid size and fluid density ρ both

equal one. This means our simple wave simulation code is

actually computing

ρ dv /

dt = vec2(L.b-R.b,B.b-T.b) = -vec2(∂p/∂x,∂p/∂y) = - del p = - ∇ p

Hey, that's exactly the leftmost terms on both sides in

Navier-Stokes!

Bulk Transport: Advection

We now move on to "v · ∇ v", the term of the Navier-Stokes

equations that represents moving fluid--this is called various

things

like convection (when driven by heat), advection (when driven by

anything else), or just "wind" or "bulk transport".

Now, "∇ v" is the gradient of the velocity: vec3( ∂v/∂x, ∂v/∂y,

∂v/∂z). This is a little odd, because velocity is already a

vector, so taking the gradient gives us a vector of vectors (a

matrix, or tensor).

Dotting this vector of vectors in "v · ∇ v" gives us a vector

again, which is good because it's being added to dv/dt, which is

also a

vector. The bottom line is:

v · ∇ v = dot(v,vec3( ∂v/∂x, ∂v/∂y,

∂v/∂z)) = v.x * ∂v/∂x + v.y * ∂v/∂y + v.z * ∂v/∂z

In English, we're dotting our vector field with its own

gradient.

This tells us how similar the vectors are to the direction of

greatest

change, which in turn says how much the value of the vector will

change

when moving in that direction. That's how "v · ∇ v"

simulates fluid transport.

Now, we could implement this by actually taking some finite

difference

approximation of ∂v/∂x and actually computing the vector v · ∇ v

at each pixel, but this approach tends to break down and go unstable

if

the velocity gets too big. The problem with the differential

approximation to transport is that it fits a linear model to the

local

velocity neighborhood; moving by more than one pixel is essentially

using linear extrapolation, which will amplify small waves in the

mesh. (The curious can read about the Courant-Fredrichs-Lewy

(CFL) condition.)

On the graphics hardware, it's

actually a lot easier to move stuff around onscreen by just changing

your texture coordinates--normally, you look "upwind" against the

flow

to see where your values are coming from:

vec4 C =

texture2D(srcTex,texCoords); /* center pixel, for vel estimate */

vec2 dir = C.xy; /* my velocity */

vec2 tc = texCoords - vel*dir; /* move "upwind" */

C = texture2D(srcTex,tc); /* advected source center pixel */

This also gives advection just like v · ∇ v, but it's more

error-tolerant than v · ∇ v, because we can advect by multiple

pixels in a single step. Jos Stam calls this technique "stable

fluids".

Overall, the bottom line on Navier-Stokes is actually pretty simple:

density * ( acceleration + advection) = pressure induced forces +

viscosity induced forces + other forces